Leaving small lanterns behind

flattening the hierarchy of what counts

There is something quietly disorienting about a five-year journal—the way time folds back on itself each morning.

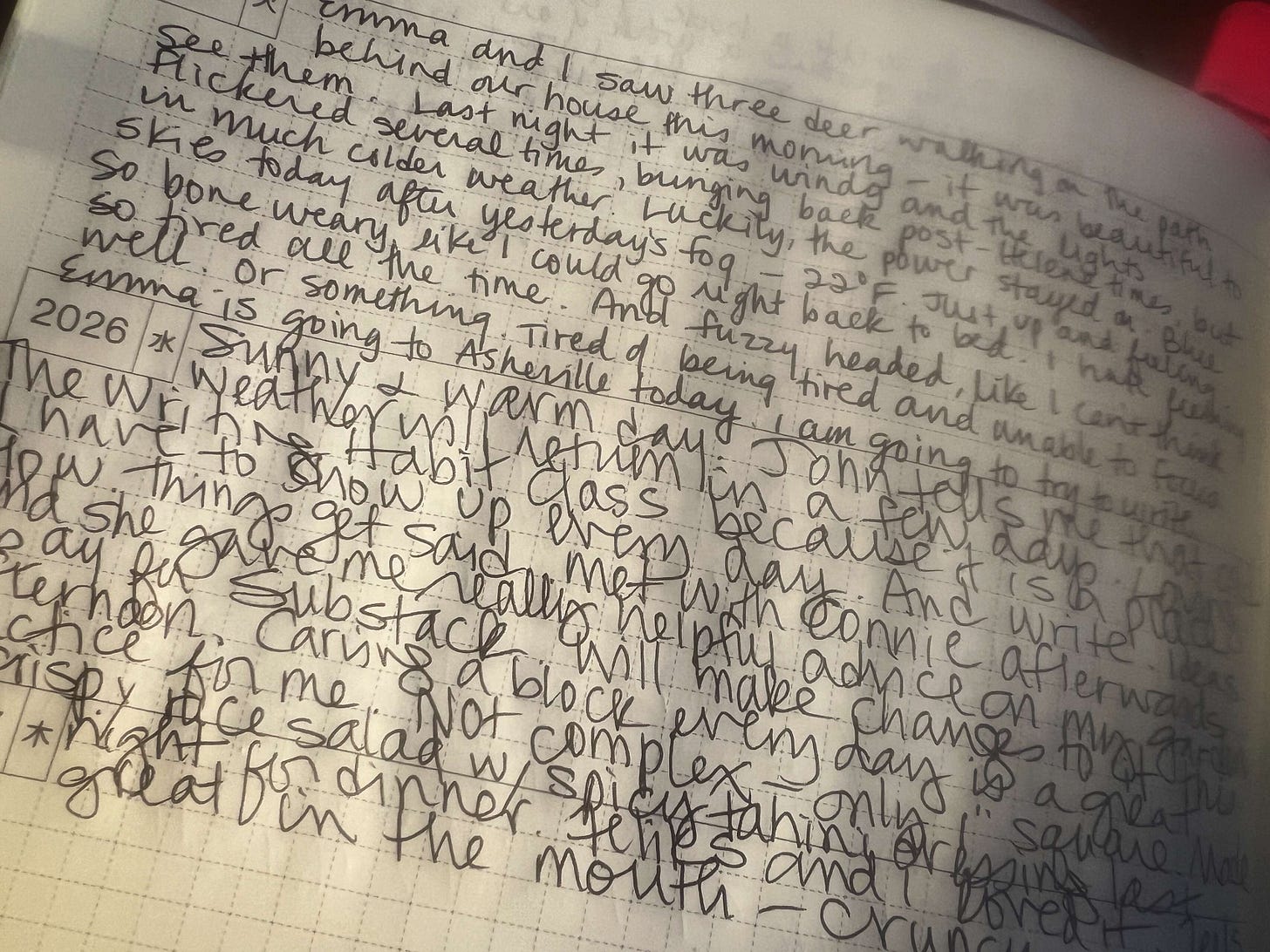

I have just begun the second year in my Hobonichi five-year journal, which means that every day now carries a faint double exposure. The first year is simple documentation. The second year introduces comparison. Each day now arrives with a shadow. Before I write a single word, I can see who I was on this date one year ago—what mattered, what I noticed, what I believed enough to record in the small, allotted space.

I write in the present while the past sits there waiting, already inscribed. Yesterday, for example: on that date in 2025, Emma and I stood together at the window and watched three deer move cautiously through the backyard, their bodies tentative and alert, stitched briefly into our ordinary afternoon. This year, on the same square of paper, Emma is not here. She lives on the West Coast, working, building a life that rarely includes these small, shared sightings.

Even my handwriting bears witness. Last year’s is small, compact, cautious—letters carefully rationed to fit the space. This year’s is expansive, looser, less worried about staying within the lines. I didn’t notice the change as it happened. I only see it because time has made a comparison for me.

That’s the strange mercy and quiet cruelty of this kind of journal: it doesn’t let you curate your past. It shows you exactly what you once wanted, what you once promised yourself, and how little some longings move on a one-year clock. To read that you needed to lose weight then and still feel that need now a year later is to encounter a familiar chorus—shame, regret, the inner reprimand that says you should have done better by now. The page becomes a mirror that does not flatter, and sometimes it feels accusatory simply by telling the truth.

But the same pages refuse to stay in that register. Threaded through the self-scolding are these bright, stubborn proofs of life: the books that held you and were worthy of being named, the affection for your small family written plainly and without irony, the recipes that landed just right and made an ordinary evening feel like an occasion. These entries don’t measure progress; they measure presence. They remind you that while some goals remain unresolved, you were still paying attention, still loving, still feeding and being fed in ways that matter. Some days are stormy and others are sunny.

What the five-year journal does seems to do—almost against our will—is flatten the hierarchy of what counts. Weight loss sits there beside a good dinner. Long-term aspirations share a line with a passing sentence about a book or a movie. Over time, the reprimands don’t disappear, but they stop being the whole story. They become one voice among many. And maybe that’s the deeper gift: not a record of self-improvement, but evidence that even in years when change feels stalled, a life is still being richly, observantly lived.

This flattening can feel almost rude. We are trained to believe that certain things should count more than others—that goals should matter more than moments, that change should outweigh continuity. But the five-year page doesn’t cooperate with that logic. It insists that a good book and an unresolved intention are equally part of a life. It insists that showing up, noticing, feeding people, loving who is near you—these are not footnotes to the “real” work of becoming better. They are the work.

There is grief in this realization, too. Emma’s absence this year is undeniable. The deer passed through without her. The page doesn’t console me about that. It simply records proximity and distance as facts. But there is also something steadying in seeing how love persists even as its logistics change. Last year’s entry is not erased by this year’s. They speak to each other. They widen the frame.

Over time, I suspect, the reprimanding entries will lose some of their sting—not because I will have finally “fixed” them, but because they will be surrounded by so much other evidence. Evidence that I was living. Evidence that I was paying attention. Evidence that joy did not wait for me to become improved before showing up.

A five-year journal is not a self-help tool. It does not cheerlead. It does not motivate. What it offers instead is a kind of moral humility. It reminds me that a life is not a straight line toward betterment, but a dense accumulation of days—some unresolved, some sweet, many both at once.

I keep writing. I write knowing that next year’s version of me will read this and feel something—perhaps tenderness, perhaps frustration, perhaps recognition. I write knowing that my handwriting may change again, that my family will rearrange itself again, that some longings will remain stubbornly intact.

And I write because there is joy in leaving these small lanterns behind: proof that I was here, that I noticed, that even when I felt stalled or disappointed in myself, I was still reading, still cooking, still loving the people closest to me. The journal doesn’t ask me to be better. It only asks me to be honest. Over time, that may be its quietest and most radical gift.

Love,

Patti

I love this. I just ordered a journal. You inspired me. Thank you for your perspective on presence and reflection.

So finely written, Patti. Living: yes! That is the work.